We can assess bank strength by asking two questions. First, how reliable are its assets? That is equivalent to saying, what is the risk that it makes a loss which might impair its ability to repay its creditors, including depositors?

The second question is, how much of the bank’s funding is from equity capital, as opposed to debt or deposits? This is equivalent to saying, if the bank does make losses, how much capacity does it have to absorb those losses through shareholder funds before there is insufficient assets left for the creditors? Capital means equity shareholder funds but can include long term (five years and greater maturity) subordinated debt.

These are separate but intertwined questions. A bank with very safe assets needs less capital. A very risky one should have high levels of capital.

But capital is an accounting item, a residual from calculating the bank’s assets minus its liabilities. So the calculation of capital arises from a judgement about the assets, which is where the EC concern arises.

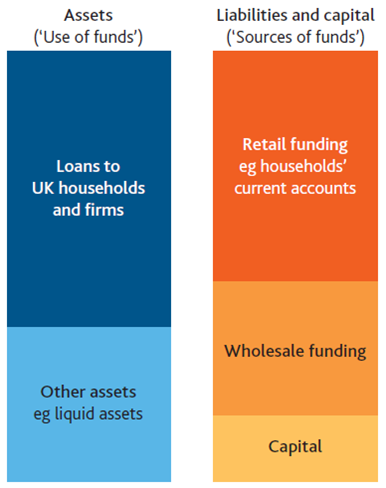

A bank traditionally had a very simple balance sheet, as shown in this diagram. Reading from right (sources of funding) to left (uses of those funds), a commercial bank takes in deposits and makes loans with them. It must have some ownership interest, which is the capital. It needs to be prudent on: i) the quality of its lending, which affects asset quality; and ii) the liquidity of its assets (because the depositors have complete freedom to asks for their funds back, in other words they expect perfect liquidity on demand. So the bank will sensibly keep some of its assets in the form of safe, liquid assets such as government bonds. If it makes an acceptable return on its loans, net of any defaults, then it can pay its depositors, pay for its operations and have a profit left for the shareholders.

Source: Bank of England

The balance sheet also shows wholesale funding as a source. Most banks issue securities, both short and long term, including bonds which are securitised on loans that the bank originally made. These can be a useful and flexible source of funding but if carried too far they expose the bank to the risk that it is over-dependent on the securities markets, which happened to the British bank Northern Rock, which was nationalised in 2007.

The global banking regulatory standard Basel III regulates all three aspects of a bank balance sheet: the proportion of assets funded with capital ; the level of liquid assets; and the balance of long term assets compared with short term liabilities, including short term securities (“the net stable funding ratio”).

Deferred tax: not as good as a loan

Life is of course a little more complex than this balance sheet. One of the assets that banks typically hold today is deferred tax. This is a credit for future taxes avoided, arising from losses made in the past or from temporary differences between the tax and accounting treatments of a transaction. Most countries allow companies to set losses against future profits, so that the tax paid in future is lower than if those losses didn’t exist. So the asset is a future reduced tax burden. So long as this is reasonably foreseeable and likely to happen, it can be put on the company’s balance sheet, though the rules vary across different accounting regimes. The opposite case can happen too in which a company records a deferred tax liability for future tax payments that are expected to fall due but haven’t yet crystallised.

You can see why a regulator might think this is not quite the same sort of asset as a loan to a creditworthy company which is fully expected to be repaid, with interest. Deferred tax is subject to two main risks. First, the bank may not make any profits, in which case it won’t have any taxes to offset the losses against. Second, tax law and rates can change in ways that may reduce the value of the tax asset in future. So deferred tax is a poorer quality asset than bank loans or high quality securities.

So in calculating the capital – the total assets minus liabilities to creditors – regulators, using Basel III rules which are being phased in from 2014 to 2019 (**), tell banks to leave out deferred tax. It appears that in some southern European countries that has not been happening. Those countries have allegedly allowed their banks to report a higher level of capital than they should, meaning they are misleading their creditors and the taxpayers as to the true financial strength of the banks.

Regulators cannot verify the quality of bank assets in detail. They have no way of checking the loan book and in any case this would go far beyond the powers and competence of a regulator. They can only set guidelines or rules on broad categories of assets. Understandably they choose to disallow deferred tax assets from the calculation of bank capital. It doesn’t mean that all the other assets are safe and reliable but it’s a reasonable rule of thumb that should help to keep the banks from failing again.

(*) Financial Times EU considers probe into unfair state aid for south European banks 6 April 2015

(**) Bank for International Settlements Basel III definition of capital – Frequently asked questions http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs204.pdf

Posted by Simon Taylor

Источник: http://www.simontaylorsblog.com/2015/04/08/how-can-we-tell-if-a-bank-is-strong/ |